The L’Aquila earthquake – Could have known better?

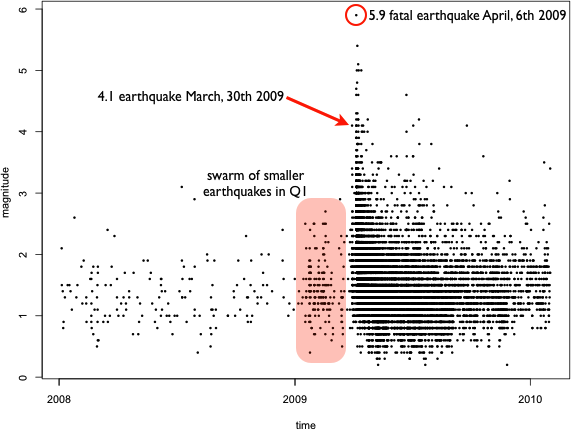

It took a while until I got the December issue of “Significance” shipped and finally got some time to read it, but the article from Jordi Prat “The L’Aquila earthquake: Science or risk on trial” immediately caught my attention. Besides the scary fact that you may end up in jail as a consulting statistician, it was Figure 1, which struck me:

Even as a statistician who always seeks exploration first, I was wondering, what a simple scatterplot smoother would look like that estimates the intensity, and whether or not it would be an indicator, of what (might have) happened.

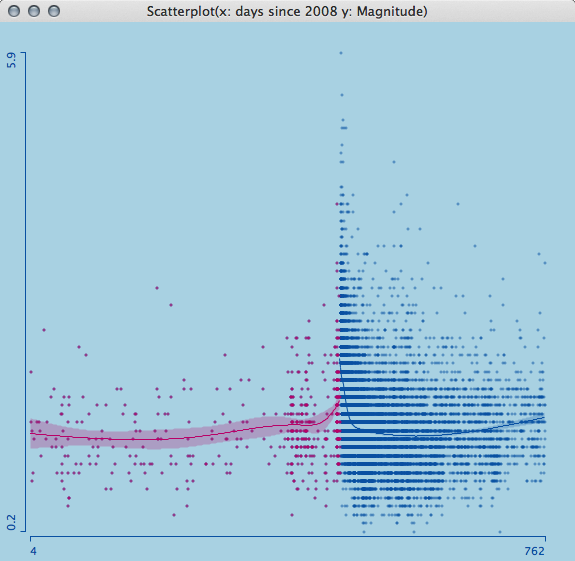

Looking at a smoothing spline with 4 degrees of freedom, separately for all the measurements before and after the earthquake, we see a sharp rise and a narrowing confidence band before April 6th 2009. As I am not a geologist, I can only interpret the raw data in this case, which I think should have alerted scientists and officials equally.

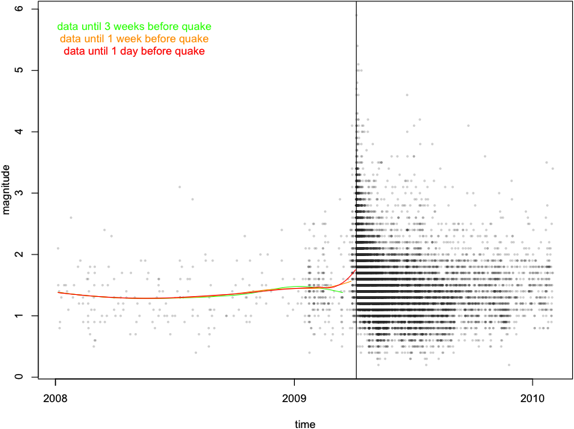

Naturally, we are always wiser after the event actually happened, so let’s look at the estimate (I use a loess-smoother with 0.65 span here) we get three week, one week and one day before the disastrous earthquake on April 6th.

Whereas three weeks before the quake things seem to calm down again, one week before the quake, the smoother starts to rise not only due to the 4.1 magnitude quake on March 30th. One day before the disaster, the gradient goes up strongly.

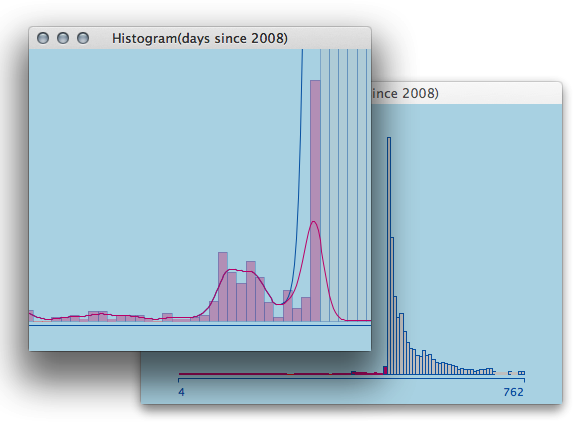

A simple zoom-in on a histogram supports the fatal hint on an apparent slow down in activity a few weeks before the earthquake.

Let me stop speculating here, but it let’s me rest more assured (as a statistician) as relatively simple data and methods do show that a stronger event might have been quite close on the evening of April 5th 2009.

I got the data from the Italian Seismological Instrumental and Parametric Data-Base and it can be accessed here. There are many articles on the web regarding the case and conviction – I only want to point here for further discussion.

“…a stronger event might have been quite close…”

I’m a geologist, and do some work in seismology, as well as in data vis. I think that an issue with this statement is that it’s always the case that a stronger event might be close. It’s not uncommon for large earthquakes to have no precursor quake or quake cluster.

Additionally it’s common for clusters to happen and not lead to a large event, though it may well be the case that the likelihood of a larger earthquake is increased during and immediately after clusters.

My point here is not to raise geologic concerns about your statistical analysis. My point is there’s an additional piece you haven’t included in your discussion. I’d modify the sentence I quoted above:

“If there is increased likelihood of destructive earthquakes during or immediately after earthquake clusters, then simple data and methods do show that a stronger event might have been quite close…”

That’s a reasonable “if” but without it, there’s no statistical argument to be made.